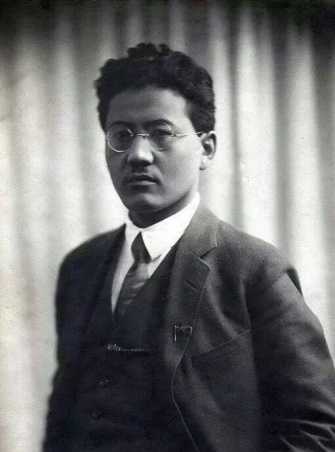

Ryskulov Turar Ryskulovich (December 26, 1894 – February 8, 1938) – was an exceptional public figure, prominent scientist, publicist, historian and diplomat. He was a leader of the national liberation movement of the Turkic-muslim peoples in Turkestan and an active spokesman for the consolidation of Turkic peoples and the idea of «Unified Turkestan». Turar Ryskulov also addressed the issues of political rights and freedoms of the native peoples of Turkestan, their equality with the rest of the population. As a representative of the ComIntern in Mongolia, he engaged in diplomatic and emissary activities, and made a significant contribution to the establishment of independent Mongolia.

Biography

T. Ryskulov was born on December 26, 1894, in the family of the herdsman Ryskul Zhylkaidarov [1] in the East Talgar volost of the Vernensky district of the Zhetysu region (present-day Almaty region). Although he was poor, Ryskul was disobedient and wayward, and he never yielded to the rich and influential people. On December 20, 1904, Turar’s father found himself as an innocent victim of defamation. Ryskul decided to take the extreme measure – the murder of the volost governor of East Talgar. After they placed Ryskul on the wanted list, the gendarmerie forcibly relocated his relatives, including 10-year-old Turar, first from Talgar to the village of Besagash, and then to Burundai. Ryskul had no choice but to voluntarily divulge himself to the police since he was concerned with the fate of his only son and the rest of the family. On December 30, police incarcerated him in the prison of Vernyi. After repeated appeals to the prison authorities, he managed to ensure that Turar would reside close to him. For more than a year, Turar was living in jail near his father. Here he was sweeping the yard, caring for livestock, and transferring the children of the head of the prison Prikhodko to study at the gymnasium of Vernyi on a cart. July 28, 1906, Ryskul, exiled to distant Siberia, had to march on the route Kopalsk-Ayaguz-Semipalatinsk by feet. [2]. The life of Ryskul and his confrontation with the colonial government were depicted in the novel «The shot on the mountain pass». Additionally, this story was retold in works of famous writers T. Nurtazin and Sh. Murtaza.

Turar had to grow up and to learn to defend himself on his own from an early age. Because he was a subject to various humiliations and oppressions by local Kazakh “bais” and Russian kulaks, it is easy to understand that the fight against national and social oppression becomes a concern of his entire life. In 1907, the relatives of Turar, who lived in the village of Merke, Aulie-Ata place, took him to their house and sent him to study at the local school for natives. The debts of Turar’s grandfather from his mother’s side on usurious loans to Merke bays became the cause of persecution on their part, to which young Turar also suffered. All the livestock of his grandfather was taken away by bays. They also forced Turar to drive grandfathers’ stocks to the bazaar, located at a distance of 30 kilometers. He was whipped along the way. Following this incident, Turar found a position as a courier to investigator A. Semashko [3].

Despite all the difficulties, Turar had showed exceptional enthusiasm for acquiring knowledge, which was remarked by teachers of the Merken school. After graduation, they sent him to the Pishpek Agricultural School, handing him a letter of recommendation. In the fall of 1914, Turar successfully graduated with a degree in gardening [4]. Immediately after graduation, Turar, who wanted to continue his studies, submitted his documents to the 1st-degree agricultural school in distant Samara. However, despite the successful passing of entrance exams the selection committee rejected him. Turar was the only Kazakh among 250 applicants. Having failed, Turar spent the whole year of 1915 with his relatives in Tulkubas. At that time, the construction of the Arys-Aulie-Ata section of the Zhetysu railway was taking place nearby. Construction was managed by a graduate of the St. Petersburg Institute, engineer M. Tynyshpaev. As a native of Zhetysu, M. Tynyshpaev had heard about the unprecedented act of the brave Ryskul. Thus, upon learning that his son Turar is in the proximity, he decided to meet him. Unordinary worldview, a broad outlook, the ability to think beyond the years of maturity and the bold nature of Turar made a pleasant impression on M. Tynyshpayev. He allocated funds from his savings to Turar, and strongly advised to him to not to stop studying. Turar always remembered this noble deed of M. Tynyshpayev, who extended his helping hand in a difficult period for him. Later, he tried to help both Mukhamedzhan himself and his son Yeskendir [5] as much as it was possible.

In Tashkent, Turar attempted to enter a pedagogical institute. His written request addressed to the inspector of educational institutions of the Turkestan Territory Solovyov was not answered. The letter addressed to the Ministry of Education of the Russian Empire did not lead to any changes either. However, these obstacles did not break Turar. Working as a gardener at the agricultural experimental station of Krasnovodsk near Tashkent, he was studying in absentia at the Tashkent Men’s Gymnasium. He was then awarded with the certificate of a volunteer listener of the 2nd category [6].

In 1916, Turar was on the side of his country, which rebelled against the colonial policy of the tsarist government [7]. During the uprising, Turar left Tashkent and arrived at Merke. In the height of the uprising, the local police arrested Turar as one of the active participants. However, failed to prove his guilt, they had to release him. The police made Turar sign the receipt that he would not engage in politics.

Upon his return to Tashkent in September 1916, T. Ryskulov received admission to take exams and entered the Tashkent Teacher’s Institute [8]. Deprived of the support of relatives, Turar was constantly in a difficult financial situation. For this reason, he had to combine studying and working as a gardener. In October 1916, he wrote a letter addressed to the director of the institute as follows: “In view of the coming winter, I would like to get clothes, such as “galoshes”, a blanket, underwear, as well as textbooks, but having no money for the acquisition of such, I have to ask you to grant me, if possible, a money allowance, since I have neither parents nor any notable person from whom assistance could be expected.1916 October 19. T. Ryskulov” [9]. The director of the institute, having considered the straitened state of Turar, ordered the allocation of 70 rubles to him. The letter shows how difficult the social and domestic situation of Turar was.

The news of the February revolution, which abolished the Romanov dynasty, found Turar in Tashkent. In the spring of 1917, he became a part of a large crowd on a hill near Merke. About one thousand armed Russian men stood on one side, and 5-6 thousand unarmed Kazakhs on the other. Representatives of the administration of the Provisional Government and the local elite assembled near the village. Having entered into negotiations with the armed Russians, T. Ryskulov found out that they demanded a compensation of half a million rubles for stealing livestock and destroying crops during the 1916 uprising. In case of refusal, they were ready to use force. T. Ryskulov answered that, after the uprising, the Russian men had taken possession of cattle, property and land of Kazakhs, who were afterwards subjected to persecution and repression by the tsarist administration. Thus, the “damage” was more than generously compensated; therefore, their claims are entirely illegal. Turar urged the Kazakhs not to pay any indemnity, saying that all actions of the local government aimed at receiving compensation payments from the Kazakh nomads were completely groundless. Angry Russian kulaks intended to stab him with a pitchfork; however, the Merke police had already arrested Turar and placed him in the local administration building. K. Adilbekov, who was engaged in mediation between Kazakhs and Russians for his profit, sought to expel T. Ryskulov out of Merke because he interfered with him. A few years later recalling this incident, the prominent statesman and politician K. Sarymuldaev wrote the following: “Karabay Adilbekov was even a supporter and initiator of payment by Kazakhs to the Merke peasants the wrong indemnity in the amount of 500,000 rubles. They did not pay only due to the intervention of Turar Ryskulov, who had returned from eviction after the 1917 revolution” [10].

Upon learning that T. Ryskulov began to engage in political affairs in Merke, his childhood friends and individual representatives of progressive youth from Aulie-Ata, Pishpek, Talas, Shu, Qordai started to gradually arrive in Merke. Around T. Ryskulov united democratically inclined representatives of not only Kazakh-Kyrgyz youth, but also local Russian intelligentsia, among whom were Sydyk Ablanov, Yskak Asimov, Russian teacher Andreev, Kenenbai Barmakov, Maksut Zhylysbaev, Karimbay Qoshmanbetov, Mamyrov, Zhuzbai Myngibaev, brothers Nurshanov, Qabylbek Sarymuldaev, Kyrgyz Turdaly Tokbaev and others. To defend the political rights and protect the social conditions of the nomadic people in a difficult period of political instability, T. Ryskulov formed an organization «Bukhara». Later, T. Ryskulov pointed out that under the influence of political transformations, the name of the society changed to “The revolutionary union of Kazakh youth”; In 1925, in his miscellany “The Revolution and the Indigenous Population of Turkestan”, he first laid out the charter and program of this organization. A few years later, in 1930, the information from this miscellany was already included in another anthology, which was compiled by S.M. Dimanshtein [11].

In the summer of 1917, T. Ryskulov returned to Tashkent and got himself actively involved in the ongoing political life. On August 2-5, a congress of Kazakhs and Kyrgyzs of the Turkestan Territory took place in Tashkent. It was attended by such well-known political figures as M. Tynyshpayev (chairman), Seitjafar Asfendiarov (honorary chairman), M. Shokay, overall, 84 people attended the general meeting [12]. T. Ryskulov, S. Utegenov, E. Kasymov, A. Kutebarov, I. Toktybaev, S. Khodjanov were elected as members of the Council of Kazakhs and Kirghiz in the Syrdarya region. To coordinate the actions of Kazakhs and Kyrgyz, a Turkestan regional central council of Kazakhs-Kyrgyzs formed. The execution of the duties of the chairman of the Council was entrusted to E. Qasymov, and T. Ryskulov became a secretary, M. Shokay was elected as honorary chairman [13].

On August 30, 1917, the Turkestan Regional Council of Kazakh Deputies was formed in Tashkent. T. Ryskulov was elected as its secretary. A little later, it was united with the Turkestan Regional Council of Russian Peasant Deputies, which in turn formed the Turkestan Regional Executive Committee of Kazakh and Russian peasant deputies. There were 6 members of the united executive committee as representatives of European nationalities; local Muslims of Turkestan were elected to the remaining 6 seats. At a meeting of the joint committee held in early September, M. Shokay was elected as a chairman [14].

In September 1917, both the Bolsheviks and the Left Social Revolutionaries began to gain strength in both Russia and Turkestan. T. Ryskulov closely followed the development of political events taking place in Russia. In November, a bloc of Bolsheviks and Left Socialist-Revolutionaries of Turkestan took power by force; two governments emerged in the province: the first was Soviet power led by Russian Bolsheviks left Socialist-Revolutionaries in Tashkent, and the second was the Muslim government in Kokand. T. Ryskulov did not enter into any contacts with the Tashkent Council, and he did not have enough money to travel to Kokand.

The dissolution of the Constituent Assembly in January 1918 and the ensuing defeat of Turkestan autonomy in February put the leaders of Turkestan in a difficult political position.

Due to the difficulties of the First World War that did not stop since 1914, the food crisis grew more and more critical in Turkestan. The uprising of 1916 and its brutal suppression led the economy of nomadic Kazakhs to collapse. The revolutionary turmoil of 1917 caused a catastrophic situation in the food industry. A particularly difficult state arose in Aulie-Ata region. Having understood that the socio-political processes taking place in Aulie-Ata district required his direct intervention, in the spring of 1917 T. Ryskulov decided to temporarily suspend his studies at the institute and return to Aulie-Ata [15].

T. Ryskulov invited members of the Bukhara Society to Aulie-Ata to discuss current political affairs with them. At that time, power in Aulie-Ata was in the hands of the Russian Bolsheviks and Left Social Revolutionaries; there were no Muslims among them. T. Ryskulov was trying to convey the hopelessness of the current situation to Kazakh youth: to save the Kazakh population from famine, it is necessary to go over to the side of the Soviet government, which concentrated all political power and military power. After this meeting, several members of Bukhara joined the party, among which was T. Ryskulov himself. In his later records, he indicated that he “joined the party in September 1917”. It is not difficult to guess that it was a political move. After the civil war, the date of joining the party began to play an important role. For this reason, T. Ryskulov, to prove his experience in the Party, was forced to indicate this date. Meanwhile, in the questionnaire of the delegate of the VIII Congress of Soviets of Turkestan, filled in the autumn of 1919, T. Ryskulov indicated that he had joined the communist party in early 1918 [16].

Kazakh leaders, led by T. Ryskulov, started to gain political weight in Aulie-Ata. Muslims, Bolsheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries of the county recognized him as a significant political figure. To help the nomadic Kazakh population, dying of famine, T. Ryskulov entered into negotiations with the Russian revolutionaries in power. On April 21, 1918, T. Ryskulov held the first congress of Aulie-Ata Kazakhs, which discussed the measures against hunger and contagious diseases, the relationship between the Kazakh and Russian populations, and the election of Kazakh deputies to the county council. By the decision of the Kazakh congress, T. Ryskulov unanimously entered the Aulie-Ata’s region soviet. From this moment, T. Ryskulov made efforts to change the national composition of the region soviet in favor of the local native population. Already in the summer of 1918, T. Ryskulov was elected chairman of the Aulie-Ata’s regional soviet directorate.

In 1918, a brutal famine swept not only the Aulie-Ata region but also the whole Turkestan region. During the years of tsarism, Turkestan was turned into a cotton-growing colony for Russia. Due to that, bread was planted in small quantities on its territory. During the civil war, grain supplies from Russia almost stopped, and as a result, the population began to starve. The Turkestan government, which consisted of Russian Bolsheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries, acquired all the grain in the region and began to provide bread only to the Russian population and soldiers in the cities, blocking Muslims from food supplies. The nomadic Kazakh population, deprived of food, began to lose stocks that devalued rapidly. Everyone who had weapons mercilessly robbed the defenseless Kazakh people. The regional authorities not only turned a blind eye to this but even openly encouraged it. T. Ryskulov quickly realized that the only way to stop this catastrophe was to join the regional government by any means necessary. At the VI Congress of Turkestan Soviets in Tashkent in the autumn of 1918, T. Ryskulov was elected a member of the Turkish Central Executive Committee and was appointed to the post of People’s Health Commissioner of the republic [17].

On November 28, 1918, T. Ryskulov intentionally quit his commissar position and formed the Central Commission to Combat Famine at the Turkish Central Executive Committee [18]. At that time, T. Ryskulov was only 24 years old, however, despite his youth; he succeeded to achieve authority in the government in a short time. He quickly became one of the prominent political figures of Turkestan. Thanks to the demands of T. Ryskulov, the Russian Bolsheviks were forced to admit the fact of the devastating famine in the Muslim population and had to allocate both food and cash. Within a few months, the Central Commission to Combat Famine was opened on a republican, county, rural municipality and city department levels. About 1,200 public catering facilities, orphanages, anti-infection hospitals and sanitary cordons were organized throughout the republic. At the invitation of T. Ryskulov, 11 thousand young patriots of the Turkestan Territory were involved in the activity in the departments of the commission on the ground. Because of the huge work that lasted for 5-6 months and required incredible efforts by the spring of 1919, the scale of hunger in Turkestan gradually began to decrease [19]. According to statistics, 1 million people were saved from imminent death [20]. The fight against famine was, first and foremost, a struggle to preserve the gene pool and the future of the nation.

In the spring of 1919, T. Ryskulov presented a plan to restrict Russian Bolsheviks, who had dominated in Turkestan since the collapse of 1917. One of the main steps towards the implementation of this plan was to create a separate political organization of Muslim Communists. It was obvious that newcomers from local Muslims needed to take power into their own hands; otherwise, it would be difficult to restore the economy of the region and to improve the social situation of the population. Planning to seize political power from the hands of the settlers, T. Ryskulov started to convince 11,000 young people who had previously shown themselves in commissions during the famine to join the Communist Party. However, most of them did not have serious managerial experience in the higher echelons of power. Besides, representatives of the older generation who refused to cooperate with the Bolsheviks, as well as the national youth under their influence, did not answer to the appeal of T. Ryskulov, hoping for a change in the political situation. Indeed, in the spring of 1919, Denikin’s army established control over the southern regions of Russia, while Kolchak’s army was around Volga and Ural, all of Siberia, as well as half of the Kazakh steppe. The Trans-Caspian region of the Turkestan Republic, the northern part of the Semirechensk region were in the hands of the White Army, while Fergana became the scene of fierce confrontation between armed military squads and parts of the Red Army. Despite the complexity of the political situation, T. Ryskulov foresaw that Bolsheviks would firmly establish themselves in the central regions of Russia. Due to that, he continued the tactics of cooperation with them.

In April 1919, T. Ryskulov created a separate Muslim bureau within the Communist Party of Turkestan. In a few months, he managed to turn it into an organization, which became able to fight the Russian Bolsheviks ruling in Turkestan. With great efforts, the Muslim bureau rose to the level of a separate political party of Muslims of Turkestan. After the overthrow of monarchical power, Muslims of Russia in an apparent or hidden manner created more than one political party and public association. However, only the Muslim bureau created by T. Ryskulov managed to leave a mark on the history of Turkic-Muslim people, achieve significant practical results, and influence Bolshevik politics in Turkestan.

The Muslim bureau did not last long, only about a year. During this time, it waged a struggle for the creation of a sovereign Turkic republic and the Muslim army [21]. The Muslim bureau played a large role in the political life of Turkestan. A devastating strike was inflicted on the ingrained chauvinist foundations in political life and the system of government in Turkestan in 1917-1919. Because of its powerful pressure, prominent representatives of chauvinism were forced to leave the region. The Muslim bureau was a centre for training state and Soviet workers. It prepared cadres of scientific and creative intelligentsia, business executives, and military specialists of different nationalities. As a result of the activity of the Muslim bureau in Turkestan, steps were made in eradicating illiteracy, creating a network of cultural and educational institutions, organizing printing and periodicals in the local language. The Muslim bureau carried out tremendous work to restore the ruined industry, specifically cotton growing as it was the main sector of economy, determining a set of measures in agriculture and animal farming.

Despite the blockade of Turkestan during the civil war, the political processes taking place in the region were under the scrutiny of the RCP(b). RCP was concerned about the policies pursued by the Muslim bureau on the national question and strove not to lose control of the region, where the vast majority of the inhabitants professed Islam. Thus, having emerged victorious in the internal political battle, the Muslim Communists, with T. Ryskulov as a leader, came across a new obstacle – the Turkestan Commission. It was an emissary body sent by the Central Committee of the RCP(b) from Moscow to Turkestan and was created on October 8, 1919, by order of the Council of People’s Commissars of the RSFSR and the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, signed by V.I. Lenin. It included such experienced revolutionaries and Bolsheviks as Sh. Eliava, M.V. Frunze, V.V. Kuibyshev, F.I. Goloshchekin and Ya.E. Rudzutak. One of the most crucial tasks entrusted to the Turkcommission was the implementation of the principles of communism in Turkestan. On November 4, 1919, members of the Turkcommission (except for M.V. Frunze) arrived in Tashkent and were immediately involved in local political life. Based on the military power of the Turkestan Front, the Turkcommission began to take measures to accumulate all state-political power in the republic.

January 21, 1920, T. Ryskulov was elected chairman of the Central Executive Committee of the Soviets of Turkestan [22], thus becoming the first leader to be a representative of the native people of Turkestan. In this position, he would work for only six months; however, this time was enough for him to turn the TurkCEC Committee into a body that was guided in its work by the specific historical and objective conditions of the region. Following the example of the TurkCEC, considering the household characteristics, traditions and customs of the local Turkic-Muslim peoples, the activities of all the commissariats were reorganized. T. Ryskulov. As chairman of the TurkCEC he started preparation and adoption of legislative acts and decrees and finding solutions for administrative, organizational and budgetary-financial issues, optimization and unification of the activities of government institutions and various commissariats. He also contributed to the elimination of the consequences of the colonial policy of the tsarist government, the return of the initial lands of natives taken by Russian peasants and Cossacks to the nomadic population. Along with this, T. Ryskulov paid great attention to issues of healthcare, education and enlightenment, culture and art. He assisted in the establishment of state institutions and helped to ensure their stable work. At the state level, T. Ryskulov was actively involved in providing financial and material assistance to Kazakh and Kyrgyz refugees of 1916 and issues of their re-evacuation from China.

The most important aim of T. Ryskulov as head of the TurkCEC was a political sovereignty of the Turkestan Republic. T. Ryskulov sought to turn Turkestan into a national state of local Turkic-speaking peoples. For this purpose, he wanted independence from the Center in resolving political, economic, diplomatic, military and cultural matters. T. Ryskulov had to fight the Turkcommission, the Revolutionary Military Council of the Turk front and the Central Committee of the RCP(b). The name of Turar Ryskulov was now closely associated with the idea of a unified Turkestan. 25 years ago, academician M. Kozybaev gave him the following estimation: “He was one of the leaders of the national liberation movement not only in the Soviet East but throughout the world. In world history, the name of T. Ryskulov stands high and burns brightly, there is no doubt that he is on a par with Sun-Yat-Sen, D. Nehru, Mustafa Kemal Pasha (Ataturk)”[23, p.239 ].

Expressing his open disagreement with the policies of the Central Committee of the RCP(b) in Turkestan, T. Ryskulov, head of the Turkestan plenipotentiary delegation, was sent to Moscow to discuss issues of Turkestan sovereignty directly with V.I. Lenin. Because of the irreconcilable position in this matter, T. Ryskulov and members of the delegation, and later his closest associates, were subjected to various political persecutions and were soon forced to leave their posts. While still in Moscow, T. Ryskulov, together with A. Baitursynov, sent V.I. Lenin a letter on the national question [24]. At the same time, on his initiative, a closed meeting was held with the participation of A. Baitursynov, M. Sultangaliev and about a dozen other significant figures of national policy to discuss general issues common to all the Turkic peoples of Russia [25].

Subjected to persecution for promoting the idea of a “Unified Turkestan” and protecting the sovereignty of the Turkestan republic, T. Ryskulov was forced to leave Turkestan in the summer of 1920 [26]. Already in September 1920, he took part in the I Congress of Oriental Peoples in Baku [27]. A keynote speech on the nation and colony at the congress was given by M. Pavlovich, member of the Collegiums of the People’s Commissariat of the RSFSR. September 5, 1920, T. Ryskulov gave an extensive speech in the debate on the report of M. Pavlovich. At meetings, T. Ryskulov noted the shortcomings of the RCP(b) policy on the national issue, organized political discussions and exchange of views. T. Ryskulov, wishing delegations from the Caucasus, Turkestan, Siberia, Mongolia, Tibet, Persia, and India to attend the congress, was holding a meeting with them at which he criticized the policy of Bolshevik Russia regarding the peoples of the East. The result of this meeting was a written appeal of 23 members of the above delegations addressed to V.I. Lenin [28].

On October 14, 1920, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the RCP(b) had a resolution “On the work of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee member T. Ryskulov,” It resulted in the declaration as follows: “The decision to introduce Ryskulov to the Board of the People’s Commissariat postponed until the opinion of all members of the Turkic Commission received”. He was sent to work in the People’s Commissariat of the RSFSR [29]. However, I.V. Stalin, who wanted to send him away from Moscow on January 6, 1921, wrote to the chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars of Azerbaijan N. Narimanov. In a letter, Stalin informed him that T. Ryskulov was sent to Baku as the plenipotentiary representative of the People’s Commissariat with the right of consultative vote to establish relations with the Center. I.V. Stalin gave N. Narimanov the following instructions regarding T. Ryskulov: “Please assist him. It will be useful for our cause if he is in the party congress as one of the delegates from Azerbaijan. Besides, he is a member of the Council of Action and his work in this institution would be useful” [30]. T. Ryskulov was in Baku only from January to April 1921. In February 1921, he participated in the III Congress of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan, and next month also in the X Congress of the RCP(b) in Moscow. In March of the same year, T. Ryskulov made several reports on the national question at the II Council of Communist Organizations of Turkic Peoples. There he assessed the policy of the Central Committee of the RCP(b) concerning the Turkic peoples of Russia as “red imperialism” [31].

In April 1921, T. Ryskulov returned to Tashkent due to his progressed lung disease for treatment with koumiss. In September 1921, at the request of the People’s Commissar’s leadership, T. Ryskulov, still being ill, was forced to return to his duties. However, in Moscow, his health condition was deteriorating, which is why he worked for a short time in the central office of the People’s Commissariat: from April 11 to March 15 and from July 17 to September 27, 1922. In the summer, his health gradually improved, and in mid-July, he returned to full-time work [32]. After a long break, T. Ryskulov was entrusted with directing a planned audit at the Moscow Institute of Oriental Studies, which was under the jurisdiction of the People’s Commissar of the RSFSR. Along with inspection of the institute, T. Ryskulov headed the State Admissions Committee for the selection of students for the 1922-1923 academic years [33]. After that, T. Ryskulov participated in the creation of the Central Publishing House of the Peoples of the East and was the first editor in chief. All the necessary documents for creating a publishing house were personally prepared by T. Ryskulov [34]. Subsequently, it was because of this publishing house that the books and works of many Kazakh scientists and educators, writers would see the light of day. It should be noted that the leader of the Alash A. Bukeikhanov was working for a long time in this publishing house. Following this, T. Ryskulov did the organization of a working faculty at the Communist University of Workers of the East, where he also gave lectures for students [35]. Continuing work in the People’s Commissariat for Education, T. Ryskulov was organizing the East Workers House in the center of Moscow. After a short time, it turned into a place of constant gathering of representatives of the Kazakh intelligentsia and youth who arrived in Moscow on duty, as well as to study [36]. On August 16, 1922, T. Ryskulov at a meeting of the Council of Nationalities of the People’s Commissar of the RSFSR, following the results of an open vote, was elected the third deputy people’s commissar. Of the 16 people who voted, all voted for the candidacy of T. Ryskulov. Despite this, on August 24, 1922, at a meeting of the Politburo, a decision was made to create a small board under the People’s Commissariat of Education, led by I.V. Stalin. G.I. Broydo became its first chairman, and the second chairman was T. Ryskulov [37]. In this position, he was entrusted with conducting political, cultural and educational work, as well as overseeing the activities of higher educational institutions of the RSFSR [38].

In the spring of 1922, the issue arose to send T. Ryskulov to Turkestan to restore the national economy of the Turkestan Territory, which was destroyed during the Civil War and the anti-Soviet armed movement. In his letter of May 14, 1922, to G.K. Ordzhonikidze I.V. Stalin recognized the significance of T. Ryskulov: “… there is no need to indulge the Turkestan communists, they did not deserve this, the last two years have shown that put together they are below Ryskulov, whom I do not mind returning” [39, p. 252]. On May 18, 1922, according to the results of I. Stalin’s report “On Turkestan-Bukhara affairs”, the Politburo adopted a resolution according to which the return of T. Ryskulov due to his illness was postponed indefinitely [40]. In September 1922, the Organizing Bureau of the Central Committee of the RCP(b) decided to appoint T. Ryskulov to the post of chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars of the Turk Republic. On October 8, 1922, T. Ryskulov, by Decree No. 442 of the Government of the Turkestan Republic, officially was appointed as a Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars of the Republic [41]; he was only 28 years old.

Agriculture was of great importance for the economy of Turkestan. Turkestan was a region in which water and land issues were equally acute but stayed unresolved. Due to the First World War, revolutionary upheavals and civil war, the irrigation system of Turkestan was ruined and needed major reconstruction. The problem of restoring the national economy depended directly on the correct resolution of the financial issue and cash injections from the Center. The development of another vital sphere, animal farming, depended on the state of pastures, hayfields and climatic conditions, and therefore required special attention from the state. There was a need to raise pedigree cattle, increase the volume of livestock trade and livestock products, and establish leather and wool processing. The problem of replenishment of livestock was critical. In connection with the catastrophic reduction in the number of livestock in the republic during the war, crop failure and famine, there was a necessity for acquiring livestock from other regions.

The restoration and development of national industries demanded the establishment of an economic union of the central Asian republics (Turkestan ASSR, Bukhara and Khorezm People’s Soviet Republics). Reconstruction of the irrigation system was possible only through the collective efforts. There was a necessity for joint strategies in industry, trade, finance and transport. All this motivated the leaders of the three countries to create an economic organization. On March 5–9, 1923, in Tashkent, at the initiative of T. Ryskulov, the First Economic Conference of the Central Asian Republics took place [42]. In his report, T. Ryskulov drew attention to similar characteristics of all three countries, emphasized their common interests in finance, foreign policy, domestic and foreign trade, transport, education and culture, cotton growing, and irrigation. He recognized the need for shared use of water resources in the region, outlined the problems of economic regionalization, protection and development of forest resources, land policy and the completion of land and water reform, production, joining forced to resolve cooperation problems, entering the single currency circulation zone, creating a single tax system and etc. At the conference, it was decided to create a Central Asian Economic Council.

T. Ryskulov paid much attention to the issues of optimizing the activity of the state administration apparatus of the Turkestan Republic. Thus it was necessary to reduce over-inflated staff in government bodies at various levels; as a result of this work, by January 1, 1923, the number of employees in the management apparatus was decreased to 11,170 people, instead of 110 thousand people in the fall of 1922 [43].

One of the areas of activity of T. Ryskulov as head of the government of the Turkestan Republic was the problems of education. To restore the national economy, it was necessary to solve issues not only of an economic nature but also to deal with the elimination of illiteracy among the population. According to the report of T. Ryskulov, at the XI Congress of Soviets of Turkestan, held in early December 1922, it was planned to release 30% of the funds from the state budget and 24% from the local budget for this cause. According to the decision of the Council of People’s Commissars and the TurkCEC of July 28, 1923, No. 13, the deadline for the elimination of illiteracy among the youth of the republic was scheduled for May 1, 1924. T. Ryskulov, on November 23, 1923, made a report on the establishment of the Bureau of Assistance to the cause Enlightenment [44] and took the leadership of it. A Culture Council is created at the Bureau, which included representatives of cultural and educational societies and national organizations [45]. T. Ryskulov made a meaningful contribution to the advancement of science and art. He was occupied with the organization and opening of research centers and institutes, the social protection of scientists. In December 1922, in order to develop Kazakh culture, the Talap society was established in Tashkent. Such famous scientists and enlighteners as Kh. Dosmukhamedov, M. Espolov, M. Tynyshpaev, M. Auezov, K. Tynystanov and others took an active part in its work.

T. Ryskulov also worked with students. As head of state, he aimed to provide all sorts of support to Turkestan students in the republic, at universities in Russia and abroad. To familiarize themselves with the circumstances of Turkestan students in Germany, at the proposal of T. Ryskulov, a delegation was organized to visit Germany in September 1923 [46]. After returning, on October 30, 1923, T. Ryskulov supported the project on the creation of the “Provisional Bureau of Student Management”. G. Beremzhanov became a chairperson [47].

As Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars, T. Ryskulov made a valuable contribution to the development of Turkestan. He laid the bases for future political and economic independence of the countries of Central Asia and Kazakhstan.

However, in early 1924, T. Ryskulov became unnecessary to the Center. The reason for this probably lies within the fact that T. Ryskulov had very principled political views. In 1920, Muslim bureau forces fought for the creation of the Turkic Soviet Republic. It was possible to break the resistance of the Turkic Commission (the first composition). Then T. Ryskulov and his political comrades-in-arms were only restrained by the commander M.V. Frunze, who arrived in Turkestan. The Turkestan delegation led by T. Ryskulov failed to convince V.I. Lenin in the correctness of their views and many prominent figures of the Muslim bureau resigned. In 1924, the Bolshevik authorities planned to conduct a national-state demarcation in Central Asia to which T. Ryskulov opposed. For this reason, at the beginning of January 1924 at the XII All-Turkestan Congress of Soviets T. Ryskulov was not elected to any responsible position. On January 16, 1924, T. Ryskulov officially resigned as chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars of the Turkestan ASSR.

Nevertheless, it did not negatively affect the authority of T. Ryskulov in the Soviet Union. By a resolution of the Politburo of January 5, 1924, he was included in two commissions for the upcoming congresses of the Soviets of the RSFSR and the USSR [48]. On January 31, 1924, at a meeting of the Politburo, «Turkestan issues» were considered, following which they made a decision: «Do not object to the unanimous proposal of the representatives of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Turkestan to recall Comrade Ryskulov from Turkestan, allow Comrade Ryskulov to remain in Turkestan until the end of March exclusively for literary work and permit Comrade Ryskulov to the ECCI (The Executive Committee of the Communist International) for work on eastern affairs» [49]. Until April 1924, T. Ryskulov worked in the archives of Tashkent and Moscow to collect documents and materials for his work on the national liberation uprising of 1916 in Turkestan [50]. Many of his scientific works published in 1925-1926 were written precisely at this time [51]. With these works, T. Ryskulov showed that if he had not been engaged in socio-political and state activities, he could have devoted himself to scientific research.

From April 15, 1924, to April 1, 1926, T. Ryskulov worked at the Comintern. On April 15, by the decision of the ECCI, T. Ryskulov served as an assistant (head) of the Middle East Department [52]. From August 1924 to July 1925, T. Ryskulov as a representative of the Comintern in Mongolia took an active part in drafting and adopting the Constitution of Mongolia, as well as in choosing the name of its first capital. July 10, 1925, the Central Committee of the MPRP expressed full confidence in T. Ryskulov’s efforts in Mongolia and gave him a positive assessment. Then, in August 1925, the People’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs of the USSR G. Chicherin expressed the opinion that his “political line is correct and deserves our support” [53, p. 284]. The activity of T. Ryskulov in Mongolia requires a diverse and separate study.

After T. Ryskulov returned from Mongolia, the highest Soviet-party leadership was considering options for his employment. By this time, T. Ryskulov held high government posts as chairman of the Muslim bureau of the RCP(b), CEC and SNK of the Turkestan ASSR, was a member of the All-Russian CEC, the Executive Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Turkestan, the Collegiums of the People’s Commissariat for Nationalities of the RSFSR, his representative in Azerbaijan, and the plenipotentiary of the Comintern and managed to establish himself as a talented organizer, skilled diplomat and experienced politician.

After some time, the All-Union Communist Party(b) decides to use T. Ryskulov in party work. During this period, the “KazKrayCom” VKP(b) worked in difficult conditions. The first secretary of the “KazKrayCom” All-Union Communist Party(b), who began to work in September 1925, F. Goloshchekin launched a major campaign against the intensified grouping. Naturally, this struggle required a lot of effort even from such an experienced politician and manager as F. Goloshchekin. At the same time, he and the leadership of the VKP(b) understood that this fight would take a lot of time and energy. This was confirmed in December at the V All-Kazakhstan Party Conference. In addition, the economy of the republic in many areas continued to remain in ruins. In terms of its level of development, the economy did not even reach the indicators of 1913. For this reason, the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks was increasingly inclined to send T. Ryskulov to work at the disposal of the “KazKrayCom”. T. Ryskulov, absent from Kazakhstan for a long time, did not object to such a prospect.

Here it is necessary to dwell in more detail on the issue of «Ryskulovism». In documents relating to 1925, there are such definitions as “Khojanovism” and “Ryskulovism”. T. Ryskulov had nothing to do with rampant grouping in Kazakhstan. Firstly, he had not worked in the KASSR before, and, secondly, his political group in the Turkestan ASSR was essentially the Muslim bureau. Muslim bureau brought together more than 11 thousand Muslim communists who had consolidated to protect the national interests of the Muslim population of Turkestan during the period of struggle against the emissary body of the Center – Turk commission. The removal of the group of T. Ryskulov by the Turkic Commission from power in 1920 was a blow to the idea of creating the Turkic Soviet state and the Communist Party of Turkic peoples. In this regard, actions aimed at protecting national interests were described as “Ryskulovism”. For this reason, accusations of Ryskulov in grouping are not justified.

Before T. Ryskulov was sent to Kazakhstan, he sent a telegram to the Central Committee of the VKP(b), to find out the political mood of F. Goloshchekin and other members of the “KazKrayCom” bureau. The telegram requested their opinion about sending T. Ryskulov to work in Kazakhstan. This was because it was well known that the relationship between the former leader of the Muslim bureau T. Ryskulov and the formerly a member of the Turkic Commission left much to be desired. Besides, it was obvious that T. Ryskulov, who had previously held higher posts and had great political authority, he was unlikely to be sent to ordinary work in Kazakhstan. This meant that someone would have to lose his position. Despite all these internal upheavals, the Bureau of the “KazKrayCom” of the VKP(b) held a meeting on February 10, 1926, named «Central Committee Telegram on the issue of using T. Ryskulov at work in Kazakhstan.” F. Goloshchekin, U. Dzhandosov, N. Nurmakov, Zh. Mynbaev, A. Sergaziev, S. Sadvakasov, U. Isaev, M. Tatimov, I. Igenov, adopted a resolution stating that members of the bureau of the “KazKrayCom” “do not object to the work of T. Ryskulov in Kazakhstan» [54].

Having received the official consent of the “KazKrayCom”, the Organizing Bureau of the Central Committee of the VKP(b) on March 3, 1926, decided on the appointment of T. Ryskulov to “KazKrayCom” with the consent of the Secretariat of the Central Committee of the VKP(b). Unfortunately, we still have not been able to find an archival document that would indicate the exact date of arrival of T. Ryskulov in Kazakhstan. However, it is known that on April 10, 1926, at a meeting of the “KazKrayCom” Bureau, which was held without the participation of T. Ryskulov, the question «On the work of Comrade Ryskulov» was considered. Based on its results, a decision was made on his appointment as the head of the press department of the “KazKrayCom”. The meeting of the “KazKrayCom” Bureau, held on April 19, happened with the participation of T. Ryskulov. At it, F. Goloshchekin made a report “On the Editorial Board of the “Enbekshi Qazaq” Newspaper”. The meeting decided to introduce U. Dzhandosov, S. Sadvakasov and T. Ryskulov to the editorial board of “Enbekshi Qazaq”, who was appointed to the post of its chief editor [55]. Consequently, T. Ryskulov arrived in Kazakhstan between April 10 and 19, 1926.

In Kazakhstan, T. Ryskulov energetically started to work. At that time, 29 periodicals were published in the country, of which 16 were in Russian, 12 in Kazakh and one in Uyghur. T. Ryskulov, as head of the regional press, made efforts to revive the work of village councils. He actively attracted periodicals in the regulation of public relations in Kazakh villages, increasing the role of the Kazakh poor in the councils. He paid special attention to the allocation of additional funds from the republican budget for the development of printing and publishing, and the improvement of the work of provincial press departments.

Despite his work, T. Ryskulov did not always correspond to party discipline. F. Goloshchekin, who was closely watching him, did not fail to take advantage of this. Even though he was the official representative of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks in Kazakhstan and the first secretary of the “KazKrayCom”, and had close relations with the Center, T. Ryskulov surpassed him in terms of both authority and political influence. Therefore, the work of T. Ryskulov in Kazakhstan could mean that soon F. Goloshchekin could lose his position. At the same time, T. Ryskulov continued to be a difficult political figure for the Center. F. Goloshchekin pursued the policy of the Center in opposing Kazakh leaders against each other. In case of Goloschekins departure, T. Ryskulov could not only consolidate them, but he could defend the interests of the republic in relation to the Centre. This can be seen from the position of T. Ryskulov regarding the ongoing campaign in Kazakhstan for the confiscation of the assets of the bais in 1928. In this regard, “removing Ryskulov” from Kazakhstan became profitable for both F. Goloshchekin and the Center itself. Secondly, most likely, F. Goloshchekin was aware that the future work of T. Ryskulov in the highest state authorities of the RSFSR could have a positive effect on Kazakhstan. Thus, after only two weeks of work in Kazakhstan, the question of transferring him to another job was raised.

At a meeting of workers of the Kazakh, Tatar and Bashkir Autonomous Republics on April 25, 1925, the issue “On the nomination of national workers in the central responsible bodies of the RSFSR” was discussed by N. Nurmakov – chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars of the Kazakh ASSR, Zh. Mynbaev – chairman of the Kazakh CEC, Akhsan Mukhametkulov – chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars of the Bashkir ASSR, Hafiz Kushaev – chairman of the CEC of the Bashkir ASSR, Shaigardan Shaymardanov – chairman of the CEC. T. Ryskulov was nominated for the position of deputy chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars of the RSCP Saitgaliev – the post of Deputy Chairman of People’s Commissars of the RSFSR Small, Biishev the Deputy People’s Commissar of Finance of the RSFSR. Zh. Mynbaev wrote to the Secretary-General of the Central Committee of the VKP(b), I.V. Stalin, Secretary V. Molotov and Chairman of the Central Control Commission V. Kuibyshev with a request for approval of the above candidates. He emphasized that this measure would improve the economic and political relations between the Center and the national republics [56].

While the Centre was considering the approval of T. Ryskulov as deputy chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars of the RSFSR, he continued to work in Kazakhstan. At the meeting of the secretariat of the “KazKrayCom” held on April 26, 1926, he made a report on the issue of the Komsomol press and announced the need to publish a separate Komsomol newspaper. He also insisted that the previous decision of the “KazKrayCom” regarding the Komsomol newspaper should be additionally submitted for discussion by the Bureau. The press department of “KazKrayCom” and Kraik Komsomol was instructed by him to make a report on the nature of the future newspaper and the means necessary for its publication by the next meeting. As a result, the party leadership of the republic decided to publish on the 4th page of the newspaper “Enbekshi Qazaq” (published since February 8, 1924) a separate supplement – the newspaper “Leninshil Zhas”. They also began to separately publish the Komsomol newspaper “Zhas Qairat” (published as an appendix on February 3, 1925, after S. Sadvakasov became its editor). Since the beginning of 1927, the newspaper “Leninshil Zhas” began to be published as an independent print organ [57].

At the same meeting, T. Ryskulov made a presentation on the Semipalatinsk state publishing house. Following the discussion of the report, it was decided to use the capabilities of the Semipalatinsk state publishing house for the benefit of the republic. He also put forward the need to establish work between the Semipalatinsk State Publishing House and the Kazakh State Publishing House. To carry out this work T. Ryskulov proposed transferring the Semipalatinsk State Publishing House to the jurisdiction of his press department under the “KazKrayCom”. This proposal was fully approved by the meeting. After a while, the Semipalatinsk state publishing house managed to turn into a publishing house of republican significance. Also at the meeting, the issue of the need to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the uprising of peasants in Kazakhstan was brought. To draw up a plan for the 10th anniversary of the national liberation uprising of 1916, a commission was formed consisting of Zh. Mynbaev, T. Ryskulov, S. Sadvakasov, U. Dzhandosov, Brudny, Ryazanov and Khangereev. Now it is known for certain that the outcome of the work of this commission, in Soviet historiography and the press, was that the history of the 1916 uprising was not only widely publicized for the first time, but also received a scientific assessment.

Shortly after the arrival of T. Ryskulov in Kazakhstan, on April 30 – May 3, 1926, the II plenary meeting of the 5th KazKrayCom committee indicated that it was necessary to repel the influence of the bays in local councils. At the plenum, T. Ryskulov especially drew attention to the fact that Kazakh bai’s penetrated the councils and hold influence in them, not because they rely on clan and family ties, but because they had economic power and leverage in their hands. This situation was an obstacle to the socio-economic development of Kazakh villages. For this reason, he expressed the view that it was necessary to increase the amount of taxation on Kazakh “bai’s” and to provide all kinds of assistance in developing unions of Kazakh peasants and workers.

May 5, 1926, in Kyzylorda in the Business Club, a grand meeting dedicated to Press Day was held. T. Ryskulov who spoke at it drew special attention to the significance and role of the press on the development of Kazakhstan in the context of perestroika. He was able to identify specific tasks that faced the republican press. It is quite obvious that the main theses of this report formed the basis of the “Plan of measures for the development of the Kazakh press” (the plan of the press department of the “KazKrayCom” – auth.), Which was adopted at a meeting of the “KazKrayCom” bureau on May 13, 1926 [58]. May 19, 1926, T. Ryskulov attended a meeting of the Secretariat of the “KazKrayCom”, where he decided to increase the subscription fee for the newspaper “Enbekshi Qazaq” to 8 million rubles a year. All of this works as evidence of his authority and the desire to bring the printing enterprise of Kazakhstan to a new qualitative level [57, p.118].

On May 27, 1926, at a meeting of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks, the question «On the third deputy chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars of the RSFSR» was considered. Following the discussion, it was decided to appoint T. Ryskulov to this post [59]. Soon, a message from the Secretary of the Central Committee of the VKP(b) V. Molotov was received by “KazKrayCom” that T. Ryskulov was approved on May 31, 1926, by the decree of the Presidium of the All-Russian CEC as deputy chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars of the RSFSR. On June 8, the newspaper Enbekshi Cossack reported about this. On the same day, T. Ryskulov took part in a meeting of the Secretariat of the “KazKrayCom” of the VKP(b). There he made reports on 5 issues and managed to get his proposals accepted, among which it is especially worth noting: the release of a new regional newspaper for Kazakh peasants; the appointment of the editor of this newspaper, Zh. Mynbaev, and his deputy, A. Baidildin; the temporary management of the press department of the “KazKrayCom” was entrusted to A. Baydildin and A. Shvergu; U. Dzhandosov was temporarily appointed the editor of the newspaper “Enbekshi Qazaq”. The verification of the scientific terminology of the Kazakh language, as well as the report of its results directly to “KazKrayCom”, was entrusted to the Printing Department [57, p.175-177].

After that, T. Ryskulov on June 14 participated in a meeting of the Secretariat of the “KazKrayCom”, and on June 16 the bureau of the “KazKrayCom”. In connection with the appointment to a new post, the Bureau of “KazKrayCom” decided to send him to the Centre [60]. Thus, the stay of T. Ryskulov in Kazakhstan lasted only 2 months. In such a short time he managed to leave a mark in the history of the printing industry of Kazakhstan.

On May 31, 1926, T. Ryskulov was appointed to the post of deputy chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars of the RSFSR, where he continuously worked until his arrest on May 21, 1937. This post was the peak of his career in the twenty-year state-political activity. Besides him, this height was never subdued by any Kazakh figure in the first half of the twentieth century. In Moscow, T. Ryskulov became a well-known political figure in the Soviet Union.

In November 1926, T. Ryskulov, without the sanction of the Central Committee of the VKP(b), held a secret meeting of national workers in Moscow [61]. For this, T. Ryskulov was subjected to various charges by the highest party authority. At the same time, all national workers who took part in the “Ryskulovs meeting” after returning to their republics received a reprimand. Because of that special demonstrative party plenums were held in Kazakhstan, Tatarstan, Bashkiria, Kyrgyzstan, and Dagestan. On these plenums, national workers were accused of national divergence.

In the years 1926-1930 T. Ryskulov headed the Turksib Construction Assistance Committee [62]. Although the official name was Turksib it was the Kazakh railway. Passing through Kulan and Semipalatinsk, it connected the East and South of Kazakhstan. The importance of Turksib for the Kazakh people and Kazakhstan is difficult to overestimate, and at present, it is a vital artery in the economy of independent Kazakhstan. Thanks to the railway, cadres of Kazakh specialist workers and engineers appeared.

Because of the bloody policy of F.I. Goloshchekin, who with the support of Stalin reigned in Kazakhstan in 1932-1933 Kazakh people suffered from famine of an unprecedented scale. Kazakhs as an ethnic group were close to extinction. Because of a violent meat-harvesting policy, out of 44 million head of cattle that nomadic Kazakhs had before the collectivization, only 4 million remained. To save his compatriots, T. Ryskulov openly addressed a letter to I.V. Stalin [63].

In the early 30s of the twentieth century in Moscow, the opposition against the violent policy of Stalin appeared. One of its groups was part of the government of the RSFSR, headed by Sergei Ivanovich Syrtsov (1893-1937). In 1929-1930, he led the Council of People’s Commissars of the RSFSR and was in good relations with T. Ryskulov. S.I. Syrtsov openly criticized the methods of I.V. Stalin on the practical implementation of the policies of industrialization and collectivization. He believed that they would certainly lead the country to a severe crisis, and people to death. He called him a «dumb head man». After the arrest of S.I. Syrtsov special agencies intensified surveillance and control. During this period, T. Ryskulov worked in Moscow in an extremely dangerous political environment. [64].

In 1936-1937, the regime of I.V. Stalin reached its climax. The last outstanding representatives of the “Leninist Guard” N. Bukharin and A. Rykov were arrested. In February and March 1937, T. Ryskulov was campaigning among delegates who arrived at the next plenary session. There he called to unite to free Bukharin and Rykov [65]. It is known that immediately after the end of this plenum, the Stalinist Great Terror gained momentum. I.V. Stalin and N. Yezhov included T. Ryskulov in the list of the highest political elite, which was to be repressed in the first place. May 21, 1937, T. Ryskulov was arrested in Kislovodsk, and under guard escorted to Moscow. After 8 months of investigation and interrogations, he was called the “enemy of the people” by the decision of the court of V. Ulrich. The trial lasted 15 minutes. On February 10, 1938, T. Ryskulov was executed under paragraph 4 of Article 58 of the Criminal Code.

After a short time, his wife, Aziza Tubekovna, was arrested and imprisoned in Butyrka. At the time of her arrest, she was pregnant. Rida Turarovna was destined to be born in prison on June 30, 1937. Two months later, the only son of T. Ryskulov, seventeen-year-old Yeskendir was soon exiled to Oneglag. For health reasons (chronic lung disease), Yeskendir had been released from the camp in 1939, but already the following year he was buried in Moscow. Stalins executioners did not spare daughters of T. Ryskulov, sending them away from their relatives. They were sent to orphanages in remote places. Aziza Tubekovna, together with her mother, spent 10 years in ALZHIR. T. Ryskulov was completely rehabilitated in 1956.

Turar Ryskulov was a major political figure, prominent public and statesman of the Turkic heritage of the first half of the twentieth century. He made a huge contribution to political freedom and economic development of the Turkic peoples of the Soviet Union. Among his contemporaries, T. Ryskulov possessed great authority. The political elite of the Soviet Union, Turkic-Muslim figures, and representatives of the intelligentsia Alash treated him with unmatched respect.

In 1919, T. Ryskulov was admitted to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Turkestan. Earlier, in December 1918, he had secretly joined the Ittihad-v-Taraki (Unity and Progress) party. This party included many famous Turkic-Muslim figures of the Turkestan region. The members of the “Ittihad-v-Taraki” party formed in Turkey carried out secret work to deploy a unified national liberation movement of the Turkic peoples. Its members in Tashkent paid close attention to T. Ryskulov, who was part of the Turkestan government. They followed the development of his political career. At a secret meeting in December 1918 in the house of Sagidulla Tursunkhodzhaev, along with the well-known pan-Turkic figures – Munavar Kara Abdurashidkhanov and Nizametdin Khodzhaev, T. Ryskulov was admitted to the Central Committee of the “Ittihad-v-Taraki” party [66]. In other words, in 1919, he openly and secretly became a member of the Central Committee of two opposing parties at once. Since that time, the idea of a “Unified Turkestan” has become the core of T. Ryskulov’s political views. Turar always remembered this idea and was persecuted all his life for it. The idea of Unified Turkestan was the cherished goal of Turar.

For about twenty years in the public service, Turar Ryskulov always sought to assist Turkic-Muslim figures, especially youth. In the autumn of 1922, T. Ryskulov made considerable efforts to release A. Bukeikhanov, who was illegally imprisoned in the Karkaraly prison, [67]. During his work in senior positions, both in Turkestan and in Moscow, T. Ryskulov tried in every way to create appropriate conditions for scientific and creative activities of political figures who were subjected to political persecution after the end of the civil war – M. Tynyshpayev, H. Dosmukhamedov, J. Dosmukhamedov, M. Zhumabaev, M. Auezov and many others. Thanks to T. Ryskulov, thousands of talented youth from the Turkestan republic got the opportunity to study at leading universities in Russia and the USSR. Later, among them, prominent statesmen grew up and brought closer the Independence Day with their work [68].

Merits

During the period of mass famine in 1918-1919, in Turkestan and 1931-1933, in Kazakhstan, T. Ryskulov made a significant contribution to saving the nomadic population from imminent death and preserving the nation’s gene pool.

T. Ryskulov was a vivid historical figure who selflessly fought for the implementation of the idea of Unified Turkestan. If the national liberation movement of the Turkic peoples can be considered a single and integral historical process, then, without any doubt, T. Ryskulov can be considered a unique phenomenon within it.

T. Ryskulov openly opposed the colonial policy towards the Turkic peoples. At the head of the Muslim bureau, he fought for the political sovereignty of the Turk Republic and the creation of a single Turkic state. By consolidating the forces of the Muslim Communists, he achieved the disarmament of the Armenian Dashnaks, Russians and Cossacks in Zhetysu, and their expulsion from Turkestan. It made a severe impact on the imperial positions of the Russian Communists in Turkestan.

T. Ryskulov was a major scientist and researcher. He is the author of about 20 books and more than 200 scientific works, among which the Muslim bureau of the RCP(b) In Turkestan, the Jetysu Issues, Lenin and the Peoples of the East, the Revolution and the Indigenous Population of Turkestan, and the Revolt of the Natives are especially noteworthy. «Central Asia in 1916», «Kazakhstan», «Kyrgyzstan», «Turksib», «Public utilities at a new stage».

T. Ryskulov was a historian and scientist who studied the history of Turkic peoples, including the Kazakh people. His major work on the history of Kazakhstan was seized during his arrest by the NKVD officers and was irretrievably lost.

Memory

The name of T. Ryskulov was already respected among the people back in the 1920s. Then, at the request of the Kazakhs of Ferghana and residents of the city of Tashkent, his name was given to local schools, and the “Koshchi” union in Aulie-Ata gave his name to their club. Naturally, in the years of the «Great Terror» the name of T. Ryskulov was forgotten.

On December 8, 1956, after the rehabilitation of T. Ryskulov, the well-known geologist M. Serikbayev began the work on returning his name, studying his life and activities, his rich scientific heritage. After gaining independence, Turar studies began to develop rapidly in Kazakhstan. A prominent writer Sh. Murtaza dedicated a series of five books to him: “The Red Arrow”, “The Star Bridge”, “Purgatory”, and “The Underworld”, which were based on historical sources and are valuable works. The play «Letter to Stalin» by Sh. Murtaza, written in the 90s of the last century, gained great fame throughout the country. In 1994, as part of the celebration of the 100th anniversary of T. Ryskulov, fundamental works devoted to his life and work were published. Among them, it is worth noting the monographic studies of O. Konyratbaev and V. Ustinov. This year, scientific and cultural events dedicated to the 125th anniversary of T. Ryskulov are held throughout the country.

3 CGARU. R-86-қ., 1-t., 1525-іs, 6-p.

6 CGARU. R-86-қ., 1-t., 1525-іs, 7-p.

8 CGARU. R-86-қ., 1-t., 1525-іs, 79-p.

9 CGARU. R-366-қ., 1-t., 29-іs, 12-p.

14 Turkestanskij kur’er. – 1917. – 6 sentjabrja. – № 199.

15 CGARU. R-366-қ.,1-t., 29-іs, 16-p.

16 CGARU. R-17-қ., 1-t., 37-іs, 147-148-p.

17 AAPRU. 60-қ., 1-t., 7-іs, 3-p.

18 CGARU. R-17-қ., 1-t., 171-іs, 118-120-p.

22 Izvestija TurCIKa (Tashkent). – 1920. – 27 janvarja. – № 18.

24 RGASPI. 5-қ., 3-t., 3-іs, 23-26-a.p.

28 RGASPI. 61-қ., 1-t., 10-іs, 7-p.

29 RGASPI. 17-қ., 3-t., 115-іs, 3-p.

30 RGASPI. 558-қ., 1-t., 5564-іs, 1-2-p.

31 RGASPI. 583-қ., 1-t., 8-іs, 65-68-p.

32 GARF. 1318-қ., 1-t., 16-іs, 121-137-p.

34 GARF. 1318-қ., 1-t., 17-іs, 134-p.

35 GARF. 1318-қ., 1-t., 17-іs, 138-a.p.

36 GARF. 1318-қ., 1-t., 17-іs, 178-p.

37 RGASPI. 17-қ., 3-t., 309-іs, 4,11-p.

38 GARF. 1318-қ., 1-t., 9-іs, 70-71-p.

40 RGASPI. 17-қ., 3-t., 293-іs, 3,9-10-p.

41 Turkestanskaja pravda (Tashkent). – 1922. – 4 nojabrja. – № 90 (246). – S. 1.

43 Turkestanskaja pravda. – 1923. – 27 marta. – № 64 (355). – S. 2-6.

44 CGARU. R-17-қ., 1-t., 369-іs, 162-p.

45 CGARU. R-17-қ., 1-t., 417-іs, 99-p.

46 Ryskulov T. Nashi studenty v Germanii // Turkestanskaja pravda. – 1923. – № 257. – 2 dekabrja.

47 CGARU. R-17-қ., 1-t., 369-іs, 59-p.

48 RGASPI. 17-қ., 3-t., 408-іs, 3-p.

49 RGASPI. 17-қ., 3-t., 414-іs, 7-p.

50 Ryskulov T. Vosstanie v Srednej Azii i Kazahstane. V 2-h chastjah. – Kzyl-Orda: 1927. – 124 s.

52 RGASPI. IKKI-495-қ., 65a-t., 11021-іs, 1-8-p.

55 APRK, 141-қ.,1-t., 486-іs, 111-p.; 1039-іs, 174-p.

56 RGASPI. 17-қ., 67-t., 327-іs, 145-146-p.

57 APRK, 141-қ., 1-t., 492-іs, 106-a.p.

58 APRK, 141-қ., 1-t., 486-іs, 147-p.

59 RGASPI. 17-қ., 3-t., 562-іs, 7-p.

60 APRK, 141-қ., 1-t., 487-іs, 1-3-p.

61 Қazbek M., Majmaқov Ғ. Құpija keңester. – Almaty: Sanat, 1999. – 336 b.

63 Қazaқ қalaj ashtyққa ұshyrady: қasіrettі zhyldar hattary. – Almaty, 1991. – 152-205 bb.

65 Haustov V., Samujel’son L. Stalin, NKVD i repressii 1936-1938 gg. – M.: ROSSPJeN, 2009. – S. 143.